For Paris Internationale 2024, a. SQUIRE shows a new body of work by Ceidra Moon Murphy which continues to interrogate state-contracted technologies, tactics and biases, informational slippages and disclosures, and the notion of a public interest.

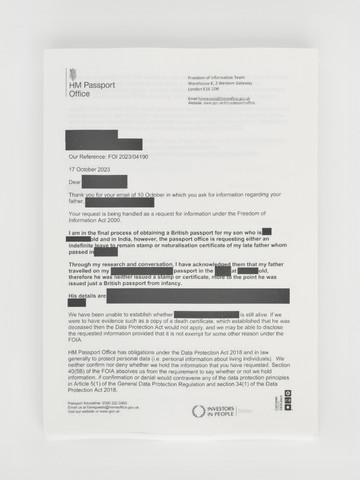

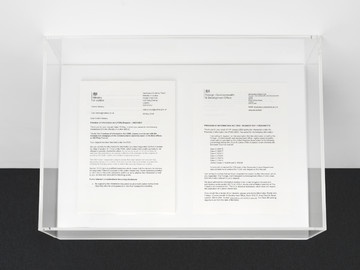

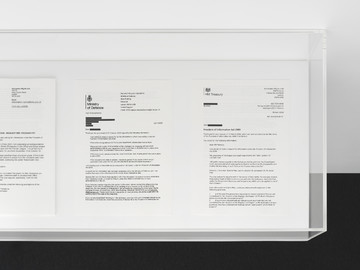

The presentation consists of 8 wall-mounted vitrines, each one containing a comprehensive series of Freedom of Information (FOI) request refusal letters sent by UK state bodies to members of the public, which in turn were obtained by Murphy by way of her own FOI requests. The work began in early February with Murphy’s submission of one such request to the Ministry of Defence. It reads:

“I would like to request the following information: A complete list of all FOI requests addressed to the Ministry of Defence that were rejected/withheld in full between October 1st 2023 and 31st January 2024. I understand these requests must be anonymised.”

In the ensuing months, Murphy entered into a stunted and pedantic dialogue with His Majesty’s Treasury, the Home Office, the Metropolitan Police, and the Ministry of Justice, among other authorities. Every refusal benchmarked her language and whittled her determination to access the desired information. These works compile and sort her findings.

The requests cited in each letter enclosed within the vitrines encompass an extensive range of topics, from statistics on bariatric surgery deaths and nuclear weapons holdings to the UK-Rwanda asylum plan. The exemption invoked with each refusal is similarly varied. The correspondence is organised according to the numerical value of the exemption applied (for instance, Section 34: Parliamentary privilege). In every resulting stack, papers are further sorted alphabetically by department, and then by date. The FOI requests become both a subject, a material and a method for Murphy, who uses them not only to point out the bureaucracies of the 2000 Freedom of Information Act, but also to uncover information withheld in other channels of official communication. Silhouetted behind each work is the Public Interest Test (PIT). As the UK Information Commissioner’s Office stipulates, ‘The public interest here means the public good.’

Mounted opposite the FOI responses is a microphone box acquired from the House of Commons, the democratically elected house of the UK Parliament. The box lies open, its contents absent.

The presentation is accompanied by a conversation between the artist and Olivia Aherne, Curator, Chisenhale Gallery.

Ceidra Moon Murphy lives and works in London. Recent exhibitions include ‘118½’, Emalin, London (2024); ‘Buffer’, a. SQUIRE, London (2023); and ‘Earwitness’, Southbank Centre, London (2022). Her work is held in the collection of KADIST, and is the subject of a forthcoming institutional solo exhibition at E-WERK Freiburg, Germany (2025).

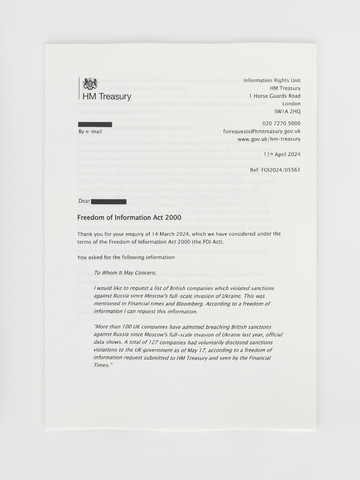

Pictured:

Ceidra Moon Murphy

PIT (S. 27, 28 and 29), 2024 [detail]

Printed documents, vitrine

Section 27: International relations.

Section 28: Relations within the United Kingdom.

Section 29: The economy.

15.5 x 81 x 40 cm

6 1/8 x 31 7/8 x 15 3/4 in

AS-MURPC-0015

Olivia Aherne: Your new body of work is the product of 46 correspondences with 15 UK government bodies over the last seven months. Through your own Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, the work brings together 564 responses to FOI requests made by members of the public. Can you describe the process of obtaining these documents?

Ceidra Moon Murphy: I didn’t know what I was looking for at the beginning, but I sent the first requests to the Ministry of Justice, the Metropolitan Police, and the Ministry of Defence at the start of February, which came out of previous work that I had been developing looking into the transparency of policing. I began by asking for an inventory of FOI requests sent to each department, where the information requested had been withheld in full. I was quite vague with the particular time frame, asking for those answered between 1st October 2023 and 31st January 2024, and initially I didn’t specify that what I was interested in finding out was what exemption the requests had been refused under.

I received replies stating that my requests were ‘vexatious’. Section 14(1) is designed to protect public authorities by allowing them to refuse any requests which have the potential to “cause a disproportionate or unjustified level of disruption, irritation or distress.”1 However, one of the responses I received was more cooperative, and disclosed that the request was vexatious because it was burdensome due to the time it would take to action. So with that information I was able to go back to my request and narrow down the time period before re-submitting.

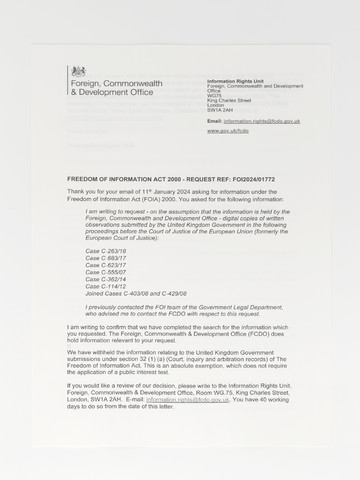

I spent about six weeks sending a variation of the same request to different departments, each time making them more specific and mimicking certain phrases or words which I noticed being used in the response letters I received. So by the time I submitted one to the Foreign Office, I had a much better understanding of what would make a successful request and how to phrase it so as not to engage any of the exemptions. The Foreign Office was the first government body to supply me with the information I requested by sending the individual response letters, with only the name of the requester redacted, as opposed to an inventory. It meant I could read exactly what information was originally being asked for by a member of the public, and what exemption(s) had been applied. By sending me the response letters rather than a spreadsheet (which is what the Cabinet Office had sent) they determined what form the work would take, and I was able to start analysing all of the exemptions applied in relation to the corresponding requests, and which exemptions were used more than others.

From that point on, I decided to forward my successful request on to other ministerial departments, adding that I was now seeking the response letters to requests where the information was denied, rather than a list.

OA: When the Freedom of Information Act was passed on 30 November 2000, it was introduced in an attempt to create a more open and transparent relationship between the government and the public. A policy framework was set up to provide clarity on legislation, process and timescales, but its clauses include incredibly ambiguous terms—’vexatious’ being one of these—which can be interpreted by civil servants with varying degrees of subjectivity.

CMM: Exactly. The term ‘vexatious’ is so subjective, and it’s completely up to the assessor whether they can apply the vexatious exemption. When the FOI White Paper was first published in 1997, there were only three exemptions that would protect the disclosure of information. As a result, authorities started to fabricate new exemptions as suited (without primary legislation). By the time the Act was actually implemented in 2000, the government had created a list of 23 reasons for exemption. Having now gone through so many response letters, it’s clear that if they don’t want to answer something, in most cases, they can find an excuse not to. Over the last seven months it’s been my intention to learn how to make it impossible for them to find an excuse. While the Act was set up for transparency, the framework is deliberately designed to restrict the parameters of that transparency.

OA: The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘vexatious’ as “causing or tending to cause annoyance, frustration, or worry”, which strikes a very particular tone, and almost any FOI request could be defined this way.

CMM: Yes. One of the responses that I received citing the vexatious exemption, stated that my request was frivolous in nature, which reading as a young woman, seemed gendered.

OA: It alludes to a kind of prying, yet the very framework has been set up to share information. In the same way language can act as a barrier to information, what are the obstacles that time and labour present?

CMM: It is a lot of work, and that is part of the reason civil servants really hate it. Section 12 sets out cost limits per request: for the central government, the limit is £600. If Section 12 is applied to a request, the FOI team first reaches out to the relevant department within the government body, and asks them to thoroughly assess time against cost, which is understandably tedious, and distracts from other work.

Each time a request is received, the authority has 20 working days to respond, but this period can be extended indefinitely. Departments are able to repeatedly ask for clarifications or to reduce the amount of information requested. My correspondence with the Home Office occurred over 5 months, and resulted in response letters from a 2-week rather than a 4-month period. Most recently I have been waiting for a response from the Ministry of Justice and with every enquiry I send, they respond with ‘we regret we are not able to respond within the designated time frame’, with no further explanation. At times it feels like a game in which they’re waiting for me to give up. This method of delay is evident in the very number of letters I have been able to procure and present. The Act could also change the way civil servants operate; they may no longer have frank conversations over email because they know that’s now public space, it’s FOI-able.

OA: This tension between public and private also plays out across exemptions, for example if it is deemed that a request has no or little relevance to a wider public interest, it may be dismissed.

CMM: Yes, when deciding to use many of the exemptions, the department utilises a Public Interest Test (PIT). In the Information Commissioner’s Office’s guidance on this, it alerts assessors to the fact that every FOI answered is in effect answered ‘to the world at large’, not just the individual.2 So there’s an assumption that anything released could enter the public domain. Therefore FOIs aren’t helpful for obtaining information on things that are specific to an individual, unless you can prove a broader public interest. Some of the response letters from the Home Office include requests for missing family documents that can act as proof for passport applications, yet because they would disclose personal information, they’re able to say no under Section 40. Section 40 is also an ‘absolute exemption’ on disclosure so there is no public interest test to apply.

OA: You have organised the request letters into stacks according to which exemption of the Freedom of Information Act was applied.

CMM: Yes, they’re arranged this way so that it’s visually clear from the size of the pile which exemptions are applied more frequently. Within the piles there are further discrepancies because each government department uses the exemptions differently. What this reveals is that this one piece of legislation, which should be uniform and used consistently, is used varyingly.

OA: When encountering the work, how much information is revealed to a viewer?

CMM: Because of how they are piled up, only one response letter is visible per exemption, the letter at the top. I’m currently in the process of selecting those letters, which ultimately change how the viewer will read the entire body of work —some are much more loaded than others.

For example, one request where information was withheld under Section 27 (International Relations), asks for communications between the Foreign Office and the British Embassy Abu Dhabi and Dubai, surrounding the ongoing legal battle relating to possible financial impropriety between Manchester City football club and the Premier League. In this case, the letter justifies the exemption in depth stating that:

“We acknowledge that releasing information on this issue would increase public knowledge about our relations with the UAE. However, the effective conduct of international relations depends upon maintaining trust and confidence between governments. This relationship of trust allows for the free and frank exchange of information on the understanding that it will be treated in confidence. If the United Kingdom does not respect such confidences, its ability to promote and protect UK interests through international relations will be hampered, this will not be in the public interest. For these reasons we consider that the public interest in maintaining this exemption outweighs the public interest in disclosure of the information.”

The reply makes it very hard to contest. In February, the Metropolitan Police sent me an extensive six-page response articulating exactly why my request was vexatious, citing various clauses of the FOI Act, which effectively silenced me. I think it was designed to be an intimidating overload of information which they know many people will struggle to navigate.

OA: The work then becomes much more about the process than the information itself. The notion of trust or trustworthiness is also striking in this context; after all, the Act was set up to tackle a lack of trust, but often doesn’t give the ‘full picture’ or prevent information from being mishandled.

CMM: Originally, when I submitted the requests asking for a complete list of FOIs that had been rejected, I was interested in the possibility of displaying information that had been withheld, but as I’ve gained more insight into the process, my attention has become much more focused on how it operates and for whom. The most recent report on the Windrush Scandal, published by the Home Office, was the outcome of FOIs which were actually withheld on the grounds that they might make certain communities lose trust in the government. Using that as an argument against disclosure contradicts the entire premise of the Act.

I think there’s often the perception that transparency is overall a good thing, and that having information made public means the public has the whole picture. So with that in mind, I think it’s important to draw attention to the fact that this information moving into the public domain is a process, and that process is inherently selective and has the potential to either deliberately, or otherwise, distort and/or manipulate. Examples of this were the dossiers handed to journalists by Tony Blair’s government in the run-up to the Iraq war, which set out to shift public perception by supposedly proving that Saddam Hussein had chemical weapons.

In one case they released raw intelligence relating to mobile labs that were manufacturing chemical weapons, information that should never be interpreted by non-experts. It shared all of the evidence but took out the intelligence assessments from MI6 which cast doubts on the interviewee’s trustworthiness. He was later proved to have lied. In another, they published information taken directly from a student’s thesis, presenting it as authoritative and without references. FOI requests are also mostly made by journalists, who have their own political leaning and agenda, some-times working directly in support of certain politicians.

OA: In your presentation at Paris Internationale, the stacks of letters are accompanied by a microphone case acquired from the Houses of Parliament. Can you describe the significance of this object, and how it speaks to the FOI requests?

CMM: The microphone case is presented as an artefact or a relic. AKG D222 microphones can be found positioned at the despatch boxes in the Commons Chamber, and are used by the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. They were first installed in the 1970s, as debates began to be broadcast by the BBC. The case contains a protective foam, yellowed from years of noise pollution. In conversation with the FOI response letters, on one side we have what we’re told and on the other side, what we’re not told.

Together the pieces explore a push and pull of control. And now that I’m deciding what to make visible in the work, I am also in control of what is of public interest. I’m curious as to what happens if the stacks of letters are rearranged by someone else in future contexts—other individuals will have different ideas of which requests and responses they want to make legible.

Murphy’s compiled Freedom of Information requests can be downloaded below: