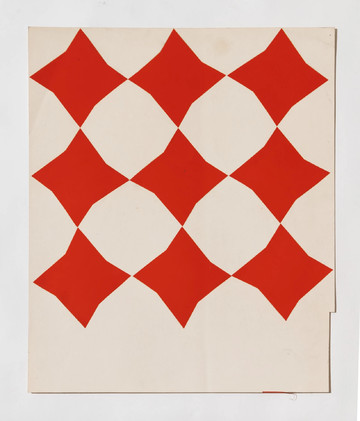

Wool

(produced by PINTON)

38 x 39¼ in (96.5 x 99.7 cm)

Edition of 3 plus 1 AP

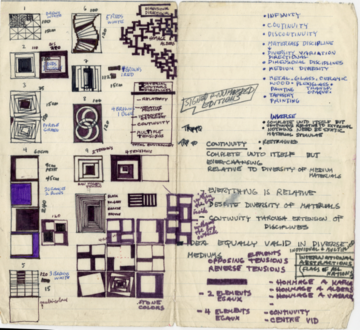

“Each work is but an element in a process to be woven into a vast world of interrelational hidden meanings […] whereby each is relative to the other, incidental to each other, interdependent upon each other […]”

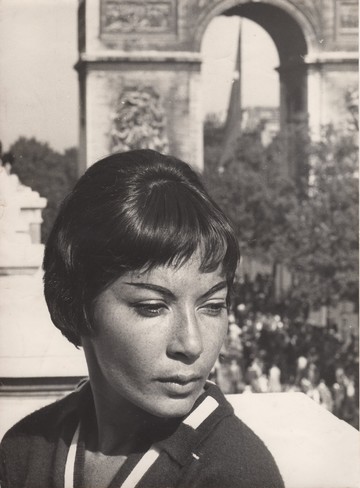

Bettina

Portrait of Bettina, 1960s

Bettina Grossman (1927–2021) lived and worked for nearly fifty years at Manhattan’s storied Chelsea Hotel.

Bettina—who went by her first name only—worked across print, sculpture, film, drawing, photography, text, and more, with each work emerging from various systematic, prolonged processes.

In December 1966, a fire in Bettina’s Brooklyn Heights studio destroyed her work up to that date. Following this devastating event Bettina went to Europe. In her notes she simply writes 1970 – Paris – Reborn.

The selection of works at Paris Internationale returns to this pivotal moment in the artist’s life and work. In part Bettina reimagined her practice through what she would describe as a “total environment”–a kind of ecosystem in which she would “prove” various hypotheses through experimentation with techniques such as tapestry, stained glass, and marble carving.

In 1971, Bettina joined the esteemed Pinton atelier to produce a distinctive series of woven tapestries. They will be presented for the first time in Paris.

Wool

(Produced by Pinton)

49½ x 38½ in

125.7 x 97.8 cm

Edition of 3 plus 1 AP

New York Times, by Alex Vadukul

Wool

(produced by Pinton)

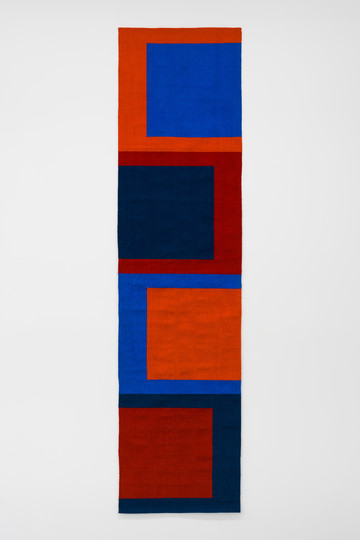

23¾ x 93¾ in

60.3 x 238.1 cm

Edition of 3 plus 1 AP

MoMA Magazine, Yto Barrada and Lucy Gullun on Bettina

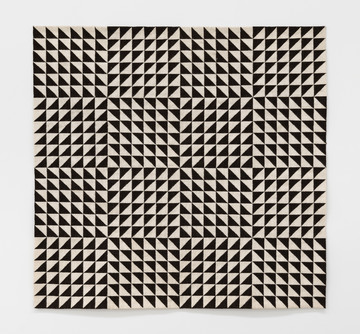

Wool

(produced by Pinton)

39¼ x 38 in

99.7 x 96.5 cm

Edition of 3 plus 1 AP

New York Magazine, by Tess Edmonson

Wool

(produced by Pinton)

28½ x 58 in

72.4 x 147.3 cm

Edition of 3 plus 1 AP

Wool

(produced by Pinton)

39¼ x 38 in

99.7 x 96.5 cm

Edition of 3 plus 1 AP

Wool

(produced by Pinton)

46 x 38 in

116.8 x 96.5 cm

Edition of 3 plus 1 AP

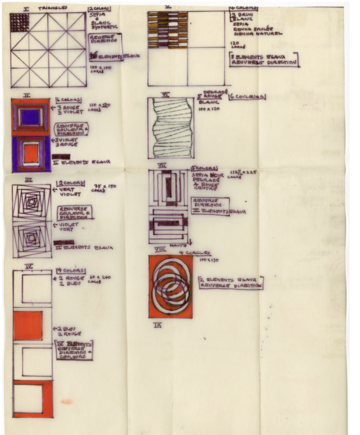

Bettina’s studies for taperstries

nut wood

4¼ x 50 x 1¾ in

10.8 x 127 x 4.4 cm

Artforum, by Noemi Smolik

nut wood

4½ x 73⅞ x 1¾ in

11.4 x 187.5 x 4.5 cm

Balcon Bettina, by Clément Dirié

nut wood

4⅜ x 66¾ x 1¾ in

11.2 x 169.5 x 4.5 cm

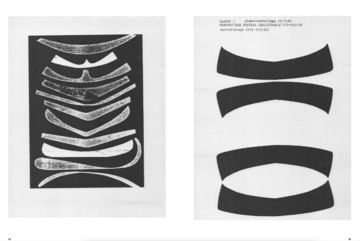

Bettina’s studies for Shango sculptures

nut wood

12 x 48⅜ x 2⅜ in

30.5 x 123 x 6 cm

Installation View

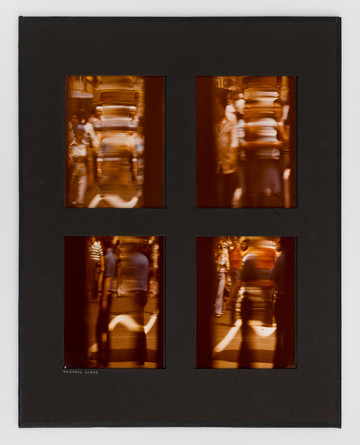

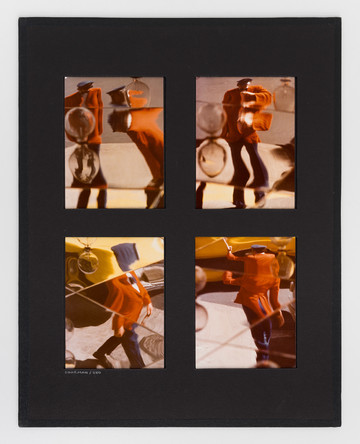

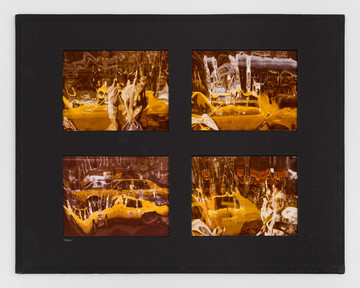

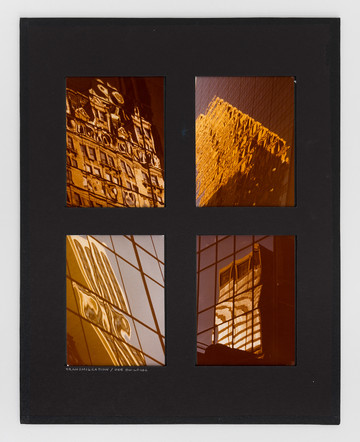

C-prints (printed and mounted by Bettina)

14 x 11 in

35.6 x 27.9 cm

Phenomenological New York (c. 1970s–c. 1980s) consists of silver gelatin prints, chromogenic prints, photographic collages, and super 8 film. This was one of two major projects Bettina made “about” New York City—the other being The Fifth Point of the Compass (1977-85). Both projects focus on activity on New York City streets, but from different perspectives. When describing the two projects, Bettina writes that one was “anthropological” (The Fifth Point of the Compass) and the other “phenomenological” (Phenomenological New York). Where The Fifth Point of the Compass comprises thousands of birds-eye view photographs of pedestrians on 23rd street, flattened against the grid of the sidewalk, and organized into alphabetical “commonalities,” Phenomenological New York focuses on movement on the street as seen through distorted reflections in the glass and metal of surrounding buildings, cars, and windows. Bettina once described her phenomenological work in this way:

“You see I was back in New York, trying to find this invisible secret. And there is a mystery here. It keeps us here. […] I found it there in the architecture. And I started photographing distortions in the architecture—not straight reflections […] And, then I found out that [with] movement, along the wall of the building, the reflections changed. Every time you move, it’s changing. And so, I was shooting a four-dimensional sequence of one single constant, which was the building, which was changing as I moved.”

Here Bettina describes her vision of movement and change in the buildings’ reflections as a glimpse of a “four-dimensional sequence.” Though they are two distinct branches of mathematics, non-Euclidean and n-dimensional (which includes the fourth dimension) geometries have typically gone hand-in-hand for artist’s seeking new spatial possibilities. One feature of fourth dimensional space is the capacity for figures to move through spatial barriers without rupture—a kind of hypermobility. Through her focus on reflective surfaces, Bettina’s figures and their movements refract onto the world around them.

-Marina Caron

C-prints (printed and mounted by Bettina)

14 x 11 in

35.6 x 27.9 cm

C-prints (printed and mounted by Bettina)

14 x 11 in

35.6 x 27.9 cm

Joel Danilewitz on Bettina, Brooklyn Rail

C-prints (printed and mounted by Bettina)

14 x 11 in

35.6 x 27.9 cm

C-prints (printed and mounted by Bettina)

14 x 11 in

35.6 x 27.9 cm

C-prints (printed and mounted by Bettina)

14 x 11 in

35.6 x 27.9 cm

C-prints (printed and mounted by Bettina)

14 x 11 in

35.6 x 27.9 cm

C-prints (printed and mounted by Bettina)

14 x 11 in

35.6 x 27.9 cm

Bettina in “Greater New York” at MoMA PS1, 2021

Options for an Angle: 24 Inconstants from One Constant

Marble

Two parts, each:

4 x 2 x 2 in.

10.2 x 5.1 x 5.1 cm.

(B008)

The suite of black-and-white marble eggs that Bettina began producing in Italy, titled “Options for an Angle: 24 Inconstants from One Constant” (1971), emerged from her theory of the “random constant.” As she explained, “By using absolutes I have demonstrated that everything is relative. That absolutes are merely constants that are equivocal and mediating and subject to change.” The constant in this series is not the egg, Bettina clarified, but the precise angle of the cut used in slicing sections from it: “I made a dozen eggs using one angle. And this one angle was consistent throughout the dozen. And I used black and white stone. And I cut through both stones at the same time using a jig, and then I relocated the white with black… And I developed these very strange curves. Each one was different. And then I found out I could go on much further than this dozen and still they would be changing and never would I have two alike.” A diagram illustrating the myriad permutations that result from the intersection of a right angle and a rotated egg appears in one of the albums that documents her projects. The permutations are multiplied further if two or more orthogonal cuts are made to the egg, which Bettina seems to have explored in another diagram and a set of half a dozen egg sculptures.

Bettina’s marble eggs call to mind Constantin Brancusi’s egg-like marble sculpture, “The Newborn” (1915), which is similarly small, freestanding, and altered by a straight slice. Like Brancusi, Bettina also photographed her sculptures, suggesting how they may be exhibited and viewed. Brancusi shot a bronze version of The Newborn in close-up to capture the reflection of his studio on its polished surface–a staging that establishes the work as a metaphor for the studio where artwork is born. Bettina photographed her eggs in pairs that show the substitution of corresponding black and white segments. Beyond documenting and displaying the sculptures, these photographs liken the sculptures’ inverted structures to the positive-negative binary of black-and-white photography itself. To take the analogy further, eggs, like photographs, are emblems of reproduction. Bettina’s first foray into three-dimensional work, then, applies photographic processes of reversal and duplication to sculpture.

-Antonia Pocock

Marble

Six parts, each:

4 x 2 x 2 in.

10.2 x 5.1 x 5.1 cm.

(B128)

paper collage

18¾ x 15¾ in

47.5 x 40 cm

paper collage

28⅜ x 22⅝ in

72 x 57.5 cm

Bettina Grossman (1927–2021) lived and worked in New York. Recent solo and two-person exhibitions include New York: 1965-98 at Ulrik, New York (2024), Balcon Bettina, Césure, Festival d’Automne, Paris (2023); Bettina: The Fifth Point of the Compass, The Hessel Museum, Annandale-on-Hudson (2023); Bettina: A Perpetual Poem of Renewal, Les Recontres de la Photographie, Arles (2022); and The Power of Two Suns with Yto Barrada at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Governors Island, (2019). Recent group exhibitions include Bad Color Combos, Kunsthalle Bielefeld (2023) and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2023), Greater New York, MoMA PS1, New York (2021), Artist’s Choice: Yto Barrada—A Raft, the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2021) and Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg (2020). The monograph Bettina was published in 2022 by Aperture, New York, and Atelier EXB, Paris. This book was developed by Yto Barrada and designer Gregor Huber in collaboration with Bettina up until her death in November 2021.

Selected Press on Bettina’s exhibition at Ulrik