For its first participation at Paris Internationale, anonymous gallery will present a solo show of artist Wendy Cabrera Rubio.

Wendy Cabrera Rubio utilizes historical and biographical materials to interrogate colonial narratives and the relationship between materiality and visual culture. In Paris, Cabrera Rubio will be offering a review of the role played by eugenics during the world fairs of the late 19th century and amateur genetic studies during the 20th century. Researching figures such as José Vasconcelos, Muriel Howorth and Luther Burbank, the proposal seeks to question contemporary notions of inheritance as well as the link between agriculture and pedagogy.

Cabrera Rubio’s plush textile works blur boundaries between high and low culture, exploring themes of food commerce, Mexican biology, and the resurgence of the extreme right through interdisciplinary collaboration and archival reinterpretation.

Wendy Cabrera Rubio (b. Mexico City, 1993, lives and works in Mexico City) is part of a generation of artists that has been invested in revisiting the history of Mexican arts and crafts with a multidisciplinary and pedagogical approach.

Pabellon Azteca, 2024

Hand embroidered felt

59 x 39.5 x 1.25 in

150 x 100 cm

In collaboration w/ Sbethlanna Glez

The Man Who Scattered Pollen Underneath the Sun I, 2024

Low temperature ceramic, acrylic box with synthetic felt

15.8 x 6 in diameter

40.1 x 15.25 cm (vase)

(with flowers - dimensions variable)

(VASE DETAILS)

In collaboration w/ Sbethlanna Glez

The Man Who Scattered Pollen Underneath the Sun II, 2024

14 x 6 in diameter

35.56 x 15.25 cm (vase)

(with flowers - dimensions variable)

In collaboration w/ Charlotte Glez

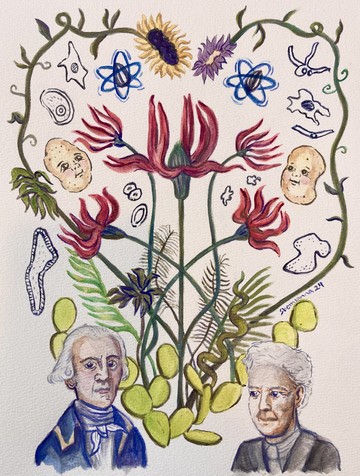

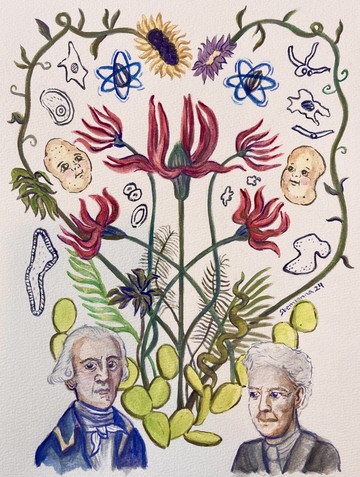

Luther Burbank and Luis Alfonso Herrera, 2024

watercolor on cotton paper

11 x 8.5 in

27.94 x 21.59 cm

A Record of Eden’s Erosion, 2024

Hand embroidered cotton and felt

17.25 x 13 in

43.8 x 33 cm

Wendy Cabrera Rubio

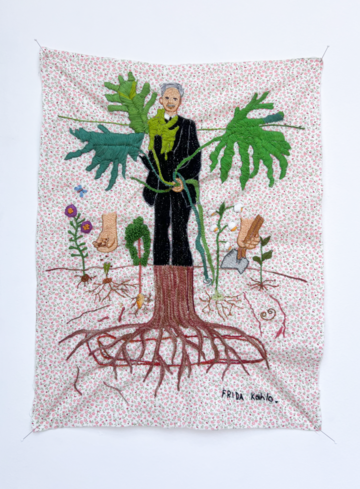

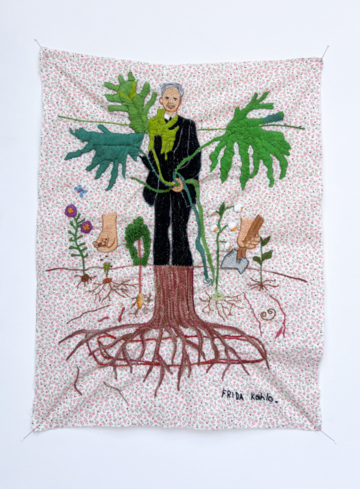

Pabellon Azteca, 2024

Hand embroidered felt

59 x 39.5 x 1.25 in

150 x 100 cm

Wendy Cabrera Rubio w/ Sbethlanna Glez

The Man Who Scattered Pollen Underneath the Sun I, 2024

Low temperature ceramic, acrylic box with synthetic felt

15.8 x 11 in

40 x 30 cm (vase)

(with flowers - dimensions variable)

Wendy Cabrera Rubio w/ Sbethlanna Glez

The Man Who Scattered Pollen Underneath the Sun II, 2024

15.8 x 11 in

40 x 30 cm (vase)

(with flowers - dimensions variable)

Wendy Cabrera Rubio w/ Charlotte Glez

Luther Burbank and Luis Alfonso Herrera, 2024

watercolor on cotton paper

11 x 8.5 in

27.94 x 21.59 cm

Wendy Cabrera Rubio

A record of Eden erosion, 2024

Hand embroidered cotton and felt

17.25 x 13 in

43.8 x 33 cm

To understand the presentation within the broader context of colonial narratives between Mexico and Paris, it’s essential to consider the role played by eugenics during the late 19th century, particularly through the world fairs, and its echoes in 20th-century amateur genetic studies. Figures such as José Vasconcelos, Muriel Howorth, and Luther Burbank provide a lens through which to question contemporary ideas of inheritance, as well as the intersection of agriculture and pedagogy.

The late 19th century world fairs were a platform where Mexico sought to present itself as a modern nation to European powers like France. These fairs celebrated technological and scientific advancements but were also permeated by eugenic ideologies, which framed European cultures as superior and positioned non-European nations as “other.” Mexico, navigating between its indigenous roots and colonial history, often found itself judged through these racist frameworks, which influenced how Mexican culture and people were depicted.

José Vasconcelos, a key figure in post-revolutionary Mexico, saw the future of the nation through the lens of mestizaje - the blending of European, indigenous, and African lineages. His writings on the “cosmic race” positioned mestizaje as a kind of eugenics, though one that sought to elevate racial mixture as a form of cultural evolution, distinct from the segregationist models in the United States and Europe. Vasconcelos’ ideas resonate with contemporary conversations about inheritance and identity, though they are tinged with an essentialism that parallels the eugenics movement‘s focus on heredity and race.

Meanwhile, figures like Muriel Howorth and Luther Burbank blurred the lines between amateur genetic experimentation and mainstream scientific discourse. Howorth, known for her fascination with nuclear energy and biology, sought to democratize scientific knowledge, promoting public engagement with genetics. Burbank, a horticulturist, was similarly engaged in the manipulation of plant heredity, breeding new plant species in an era when the boundaries between agriculture and eugenics were often porous. Burbank’s plant experiments, though focused on agriculture, paralleled the way eugenicists viewed human heredity, further intertwining nature and nurture.

There is similarly a relationship between artists of the time. Artists such as Frida Kahlo reappropriated her indigenous heritage, often woven into her paintings, can be seen as a subversion of colonial ideologies. Frida Kahlo’s work for instance, a deeply personal exploration of her own body, heritage, and pain can be seen as a counterpoint to these more rigid and reductive interpretations of heredity. Her self-portraits often incorporate elements of nature, plants, animals, and the earth as a way to reclaim and transform the narratives imposed upon her body and identity. She subverts the scientific and colonial discourses that sought to categorize and control human bodies, particularly through her focus on physical suffering and reproductive struggles, which she framed not as failures but as part of a broader dialogue about identity, inheritance, and survival.

In linking agriculture and pedagogy, Wendy Cabrera Rubio and Sbethlanna González’s proposal questions the ways in which knowledge is cultivated, transmitted, and transformed. Just as Burbank’s genetic experiments sought to breed new plant varieties, educational systems have often been shaped by ideas of social engineering, determining what kinds of knowledge should be cultivated in different populations. Vasconcelos’ work in Mexico’s education system sought to blend European and indigenous traditions, while also asserting a racial hierarchy. Cabrera Rubio’s engagement with indigenous and folk traditions, however, reveals the potential of inheritance as a form of resistance and renewal, challenging the rigid frameworks of eugenics and colonialism alike.

Ultimately, the convergence of these ideas - eugenics, agriculture, pedagogy, and artistic expression - allows us to question how contemporary notions of inheritance and identity are shaped by both biological and cultural forces. Through Cabrera’s work and the historical backdrop of figures like Vasconcelos, Howorth, and Burbank, we are invited to reconsider the links between the cultivation of life, knowledge, and the self, as well as the narratives that continue to shape them.